An unwelcome visitor to the Valley

Written by Sue Perry

One of the founding aims of the Friends is to encourage visitors to our World Heritage site to enjoy its serene ambience, its history and its flora and fauna. As we have been able to venture farther afield, the Valley has been busy with many more visitors over recent weeks and there is no better feeling than meeting people who are enjoying the valley as much as I do. However, visitors last Friday may have wondered why a small determined group, under our Ranger’s supervision were apparently vandalising swathes of undergrowth and uprooting pretty pink flowers so loved by the bees. This is our unwelcome visitor, Himalayan Balsam.

Himalayan Balsam, now commonly seen throughout Cornish waterways and countryside is a close relative of the ‘Busy Lizzie’ that was such a garden favourite when I was growing up (perhaps less so these days). Unlike its garden cousin, Himalayan Balsam or Impatiens Glandulifera really does live up to its common name of being very, very, busy. It started life in this country as an import by Victorian gardeners; not only was there an intricate, beautiful flower to commend it, but this annual plant grew tall, loved damp shade and flowered from June all the way to October. Common names such as ‘Policeman’s Helmet’ ‘Jumping Jack’ and ‘Kiss me on the Mountain’ suggest a popular fondness for it or even an air of romance.

While gardeners might appreciate the flowers, children (and perhaps more than a few grown-ups) especially love the ‘Jumping Jack’ seedpods, each containing around 800 seeds that explode when ripe, shooting contents up 22 feet into the air, and lend it the Latin name ‘Impatiens’. In its native India and Pakistan, the seeds are used in cooking to add a nutty flavour to curry or cakes and they have even been used to flavour gin, which on adding tonic water changes the gin colour from clear to pink, just like its flowers. Flower heads too can be used to make jellies and wine, while young flowers and leaves can be used in salads or the leaves distilled to make a treatment for anxiety. Then once all the plant has been put to work, the hollow stem that remains serves as a perfectly good straw through which to sip the gin!

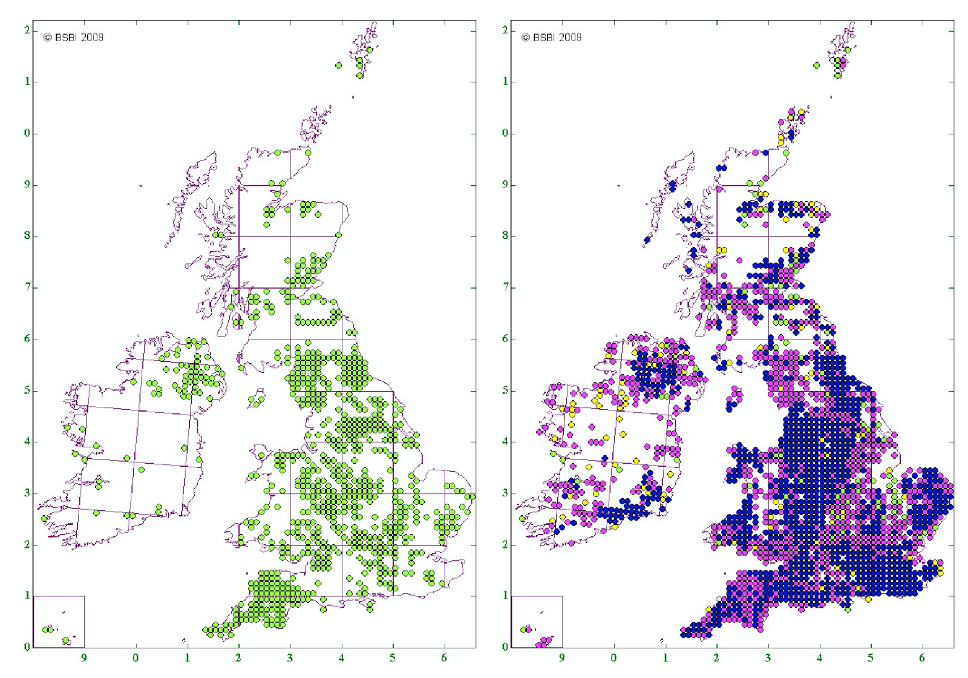

So how come such an apparently virtuous and useful plant is so unwelcome in the Valley? Having escaped from domestic gardens it has been exceptionally busy spreading unchecked throughout the UK as the maps from 1970 and 2000 show below. It has no natural predators to keep in in check and its preference for damp ground allows it to spread rapidly along our watercourses, while its seeds, which can survive in the soil for up to 3 years, are blown in on the wind, quickly colonising open waste ground. Its tall dense growth out-competes most other plants so that once the plant dies at the end of summer the ground is left exposed and prone to erosion, especially on riverbanks, leading to increased sedimentation in rivers in some areas and flooding in others. Fish and other aquatic life are suffocated in the rivers and reduced biodiversity generally leads to falling numbers and differing types of invertebrate feeders, and while bees love to visit the flowers, there are concerns that they favour the Balsam flower too much over other native flowers. Such is the negative ecological impact it is now an offence to plant it in the wild.

UK distribution 1970 UK distribution 2000

So that’s why our work party last Friday could be seen deep in the boggy undergrowth near Ponts’ Mill and the lower tramway undertaking a case of ‘extreme weeding’. Fortunately, there is one way that Himalayan Balsam is not so busy or impatient, and that is laying down roots; these are very shallow and with a firm grasp at the base of the stem the whole plant can be uprooted with one pull. Timing is important though, as enough plant needs to be visible and identifiable but pulled before it sets seed, so June and July are the best months for ‘Balsam bashing’. Once it is uprooted the stem needs to be folded and crushed and preferably left out in the sun to dry out and die, otherwise there is a risk that the plant will re-root and continue to set seed. I came across a few sites, where someone had done a great job of pulling up but had left the stems on the ground intact where the wet weather had allowed them to survive and continue flowering. It is also vital to get the root out or to cut as close to the root as possible, otherwise it will re-shoot. Where there were really dense clumps these were left for the scythe expertly wielded by Ranger Jenny, but single stems growing amid bracken needed the crack squad of balsam bashers to go in, and in my case disappear in places where the bracken and Balsam exceeded 5 or 6 feet with stems that could be used for plumbing rather than sipping gin!

It may seem a labour-intensive method of controlling its spread, but in a confined area such as the Valley it can be surprisingly effective and our group of 5 managed to clear a considerable area, while those areas cleared in previous years remain relatively free of infestation. The problem is always that seed will find its way in from elsewhere, on the breeze or from waterways upstream. Personally, in the Valley I prefer physical weeding as opposed to chemicals or even biological control; there are trials of a fungal rust that can halt prevent spread and if successful may provide a form of national control. Time will tell. In the meantime, I will continue to uproot any unwelcome visitors either as part of an organised work party or whenever I encounter them on my walks. So, when out walking the Valley, should you see from the corner of your eye a trembling pink flower amongst the tall bracken, perhaps take a closer look, you might find a very short woman wrestling a very large flower from the ground!